Chapter 10Modules

The ideal program has a crystal clear structure. The way it works is easy to explain, and each part plays a well-defined role.

A typical real program grows organically. New pieces of functionality are added as new needs come up. Structuring—and preserving structure—is additional work, work which will only pay off in the future, the next time someone works on the program. So it is tempting to neglect it, and allow the parts of the program to become deeply entangled.

This causes two practical issues. Firstly, understanding such a system is hard. If everything can touch everything else, it is difficult to look at any given piece in isolation. You are forced to build up a holistic understanding of the whole thing. Secondly, if you want to use any of the functionality from such a program in another situation, rewriting it may be easier than trying to disentangle it from its context.

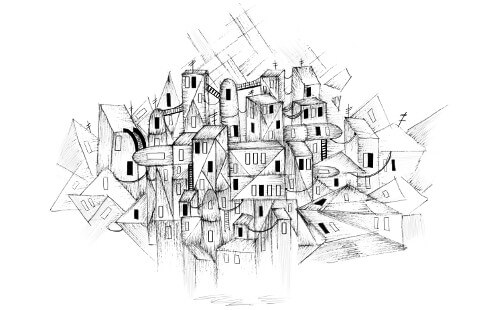

The term “big ball of mud” is often used for such large, structureless programs. Everything sticks together, and when you try to pick out a piece, the whole thing comes apart and your hands get dirty.

Modules

Modules are an attempt to avoid these problems. A module is a piece of program that specifies which other pieces it relies on (its dependencies) and which functionality it provides for other modules to use (its interface).

Module interfaces have a lot in common with object interfaces, as we saw them in Chapter 6. They make part of the module available to the outside world and keep the rest private. By restricting the ways in which modules interact with each other, the system becomes more like LEGO, where pieces interact through well-defined connectors, and less like mud, where everything mixes with everything.

The relations between modules are called dependencies. When a module needs a piece from another module, it is said to depend on that module. When this fact is clearly specified in the module itself, it can be used to figure out which other modules need to be present to be able to use a given module and to automatically load dependencies.

To separate modules in that way, each needs it own private scope.

Just putting your JavaScript code into different files does not satisfy these requirements. The files still share the same global namespace. They can, intentionally or accidentally, interfere with each other’s bindings. And the dependency structure remains unclear. We can do better, as we’ll see later in the chapter.

Designing a fitting module structure for a program can be difficult. In the phase where you are still exploring the problem, trying out different things to see what works, you might want to not worry about it too much, since it can be a big distraction. Once you have something that feels solid, that’s a good time to take a step back and organize it.

Packages

One of the advantages of building a program out of separate pieces, and being actually able to run those pieces on their own, is that you might be able to apply the same piece in different programs.

But how do you set this up? Say I want to use the parseINI function from Chapter 9 in another program. If it is clear what the function depends on (in this case, nothing), I can just copy all the necessary code into my new project and use it. But then, if I find a mistake in that code, I’ll probably fix it in whichever program I’m working with at the time and forget to also fix it in the other program.

Once you start duplicating code, you’ll quickly find yourself wasting time and energy moving copies around and keeping them up-to-date.

That’s where packages come in. A package is a chunk of code that can be distributed (copied and installed). It may contain one or more modules, and has information about which other packages it depends on. A package also usually comes with documentation explaining what it does, so that people who didn’t write it might still be able to use it.

When a problem is found in a package, or a new feature is added, the package is updated. Now the programs that depend on it (which may also be packages) can upgrade to the new version.

Working in this way requires infrastructure. We need a place to store and find packages, and a convenient way to install and upgrade them. In the JavaScript world, this infrastructure is provided by NPM (npmjs.org).

NPM is two things: an online service where one can download (and upload) packages, and a program (bundled with Node.js) that helps you install and manage them.

At the time of writing, there are over half a million different packages available on NPM. A large portion of those are rubbish, I should mention, but almost every useful, publicly available package can be found on there. For example, an INI file parser, similar to the one we built in Chapter 9, is available under the package name ini.

Chapter 20 will show how to install such packages locally using the npm command-line program.

Having quality packages available for download is extremely valuable. It means that we can often avoid reinventing a program that a hundred people have written before, and get a solid, well-tested implementation at the press of a few keys.

Software is cheap to copy, so once someone has written it, distributing it to other people is an efficient process. But writing it in the first place is work, and responding to people who have found problems in the code, or who want to propose new features, is even more work.

By default, you own the copyright to the code you write, and other people may only use it with your permission. But because some people are just nice, and because publishing good software can help make you a little bit famous among programmers, many packages are published under a license that explicitly allows other people to use it.

Most code on NPM is licensed this way. Some licenses require you to also publish code that you build on top of the package under the same license. Others are less demanding, just requiring that you keep the license with the code as you distribute it. The JavaScript community mostly uses the latter type of license. When using other people’s packages, make sure you are aware of their license.

Improvised modules

Until 2015, the JavaScript language had no built-in module system. People had been building large systems in JavaScript for over a decade though, and they needed modules.

So they designed their own module systems on top of the language. You can use JavaScript functions to create local scopes, and objects to represent module interfaces.

This is a module for going between day names and numbers (as returned by Date’s getDay method). Its interface consists of weekDay.name and weekDay.number, and it hides its local binding names inside the scope of a function expression that is immediately invoked.

const weekDay = function() { const names = ["Sunday", "Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday", "Saturday"]; return { name(number) { return names[number]; }, number(name) { return names.indexOf(name); } }; }(); console.log(weekDay.name(weekDay.number("Sunday"))); // → Sunday

This style of modules provides isolation, to a certain degree, but it does not declare dependencies. Instead, it just puts its interface into the global scope and expects its dependencies, if any, to do the same. For a long time this was the main approach used in web programming, but it is mostly obsolete now.

If we want to make dependency relations part of the code, we’ll have to take control of loading dependencies. Doing that requires being able to execute strings as code. JavaScript can do this.

Evaluating data as code

There are several ways to take data (a string of code) and run it as part of the current program.

The most obvious way is the special operator eval, which will execute a string in the current scope. This is usually a bad idea because it breaks some of the properties that scopes normally have, such as it being easily predictable which binding a given name refers to.

const x = 1; function evalAndReturnX(code) { eval(code); return x; } console.log(evalAndReturnX("var x = 2")); // → 2

A less scary way of interpreting data as code is to use the Function constructor. It takes two arguments: a string containing a comma-separated list of argument names and a string containing the function body.

let plusOne = Function("n", "return n + 1;"); console.log(plusOne(4)); // → 5

This is precisely what we need for a module system. We can wrap the module’s code in a function and use that function’s scope as module scope.

CommonJS

The most widely used approach to bolted-on JavaScript modules is called CommonJS modules. Node.js uses it, and is the system used by most packages on NPM.

The main concept in CommonJS modules is a function called require. When you call this with the module name of a dependency, it makes sure the module is loaded and returns its interface.

Because the loader wraps the module code in a function, modules automatically get their own local scope. All they have to do is call require to access their dependencies, and put their interface in the object bound to exports.

This example module provides a date-formatting function. It uses two packages from NPM—ordinal to convert numbers to strings like "1st" and "2nd", and date-names to get the English names for weekdays and months. It exports a single function, formatDate, which takes a Date object and a template string.

The template string may contain codes that direct the format, such as YYYY for the full year and Do for the ordinal day of the month. You could give it a string like "MMMM Do YYYY" to get output like “November 22nd 2017”.

const ordinal = require("ordinal"); const {days, months} = require("date-names"); exports.formatDate = function(date, format) { return format.replace(/YYYY|M(MMM)?|Do?|dddd/g, tag => { if (tag == "YYYY") return date.getFullYear(); if (tag == "M") return date.getMonth(); if (tag == "MMMM") return months[date.getMonth()]; if (tag == "D") return date.getDate(); if (tag == "Do") return ordinal(date.getDate()); if (tag == "dddd") return days[date.getDay()]; }); };

The interface of ordinal is a single function, whereas date-names exports an object containing multiple things—the two values we use are arrays of names. Destructuring is very convenient when creating bindings for imported interfaces.

The module adds its interface function to exports, so that modules that depend on it get access to it. We could use the module like this:

const {formatDate} = require("./format-date"); console.log(formatDate(new Date(2017, 9, 13), "dddd the Do")); // → Friday the 13th

We can define require, in its most minimal form, like this:

require.cache = Object.create(null); function require(name) { if (!(name in require.cache)) { let code = readFile(name); let module = {exports: {}}; require.cache[name] = module; let wrapper = Function("require, exports, module", code); wrapper(require, module.exports, module); } return require.cache[name].exports; }

In this code, readFile is a made-up function that reads a file and returns its contents as a string. Standard JavaScript provides no such functionality—but different JavaScript environments, such as the browser and Node.js, provide their own ways of accessing files. The example just pretends that readFile exists.

To avoid loading the same module multiple times, require keeps a store (cache) of already loaded modules. When called, it first checks if the requested module has been loaded and, if not, loads it. This involves reading the module’s code, wrapping it in a function, and calling it.

The interface of the ordinal package we saw before is not an object, but a function. A quirk of the CommonJS modules is that, though the module system will create an empty interface object for you (bound to exports), you can replace that with any value by overwriting module.exports. This is done by many modules to export a single value instead of an interface object.

By defining require, exports, and module as parameters for the generated wrapper function (and passing the appropriate values when calling it), the loader makes sure that these bindings are available in the module’s scope.

The way the string given to require is translated to an actual filename or web address differs in different systems. When it starts with "./" or "../", it is generally interpreted as relative to the current module’s filename. So "./ would be the file named format-date.js in the same directory.

When the name isn’t relative, Node.js will look for an installed package by that name. In the example code in this chapter, we’ll interpret such names as refering to NPM packages. We’ll go into more detail on how to install and use NPM modules in Chapter 20.

Now, instead of writing our own INI file parser, we can use one from NPM:

const {parse} = require("ini"); console.log(parse("x = 10\ny = 20")); // → {x: "10", y: "20"}

ECMAScript modules

CommonJS modules work quite well and, in combination with NPM, have allowed the JavaScript community to start sharing code on a large scale.

But they remain a bit of a duct-tape hack. The notation is slightly awkward—the things you add to exports are not available in the local scope, for example. And because require is a normal function call taking any kind of argument, not just a string literal, it can be hard to determine the dependencies of a module without running its code.

This is why the JavaScript standard from 2015 introduces its own, different module system. It is usually called ES modules, where ES stands for ECMAScript. The main concepts of dependencies and interfaces remain the same, but the details differ. For one thing, the notation is now integrated into the language. Instead of calling a function to access a dependency, you use a special import keyword.

import ordinal from "ordinal"; import {days, months} from "date-names"; export function formatDate(date, format) { /* ... */ }

Similarly, the export keyword is used to export things. It may appear in front of a function, class, or binding definition (let, const, or var).

An ES module’s interface is not a single value, but a set of named bindings. The preceding module binds formatDate to a function. When you import from another module, you import the binding, not the value, which means an exporting module may change the value of the binding at any time, and the modules that import it will see its new value.

When there is a binding named default, it is treated as the module’s main exported value. If you import a module like ordinal in the example, without braces around the binding name, you get its default binding. Such modules can still export other bindings under different names alongside their default export.

To create a default export, you write export default before an expression, a function declaration, or a class declaration.

export default ["Winter", "Spring", "Summer", "Autumn"];

It is possible to rename imported binding using the word as.

import {days as dayNames} from "date-names"; console.log(dayNames.length); // → 7

At the time of writing, the JavaScript community is in the process of adopting this module style. But it has been a slow process. It took a few years, after the format was specified, for browsers and Node.js to start supporting it. And though they mostly support it now, this support still has issues, and the discussion on how such modules should be distributed through NPM is still ongoing.

Many projects are written using ES modules and then automatically converted to some other format when published. We are in a transitional period in which two different module systems are used side-by-side, and it is useful to be able to read and write code in either of them.

Building and bundling

In fact, many JavaScript projects aren’t even, technically, written in JavaScript. There are extensions, such as the type checking dialect mentioned in Chapter 8, that are widely used. People also often start using planned extensions to the language long before they have been added to the platforms that actually run JavaScript.

To make this possible, they compile their code, translating it from their chosen JavaScript dialect to plain old JavaScript—or even to a past version of JavaScript—so that old browsers can run it.

Including a modular program that consists of 200 different files in a web page produces its own problems. If fetching a single file over the network takes 50 milliseconds, loading the whole program takes 10 seconds, or maybe half that if you can load several files simultaneously. That’s a lot of wasted time. Because fetching a single big file tends to be faster than fetching a lot of tiny ones, web programmers have started using tools that roll their programs (which they painstakingly split into modules) back into a single big file before they publish it to the Web. Such tools are called bundlers.

And we can go further. Apart from the number of files, the size of the files also determines how fast they can be transferred over the network. Thus, the JavaScript community has invented minifiers. These are tools that take a JavaScript program and make it smaller by automatically removing comments and whitespace, renaming bindings, and replacing pieces of code with equivalent code that take up less space.

So it is not uncommon for the code that you find in an NPM package or that runs on a web page to have gone through multiple stages of transformation—converted from modern JavaScript to historic JavaScript, from ES module format to CommonJS, bundled, and minified. We won’t go into the details of these tools in this book, since they tend to be boring and change rapidly. Just be aware that the JavaScript code that you run is often not the code as it was written.

Module design

Structuring programs is one of the subtler aspects of programming. Any nontrivial piece of functionality can be modeled in various ways.

Good program design is subjective—there are trade-offs involved, and matters of taste. The best way to learn the value of well-structured design is to read or work on a lot of programs and notice what works and what doesn’t. Don’t assume that a painful mess is “just the way it is”. You can improve the structure of almost everything by putting more thought into it.

One aspect of module design is ease of use. If you are designing something that is intended to be used by multiple people—or even by yourself, in three months when you no longer remember the specifics of what you did—it is helpful if your interface is simple and predictable.

That may mean following existing conventions. A good example is the ini package. This module imitates the standard JSON object by providing parse and stringify (to write an INI file) functions, and, like JSON, converts between strings and plain objects. So the interface is small and familiar, and after you’ve worked with it once, you’re likely to remember how to use it.

Even if there’s no standard function or widely used package to imitate, you can keep your modules predictable by using simple data structures and doing a single, focused thing. Many of the INI-file parsing modules on NPM provide a function that directly reads such a file from the hard disk and parses it, for example. This makes it impossible to use such modules in the browser, where we don’t have direct file system access, and adds complexity that would have been better addressed by composing the module with some file-reading function.

Which points to another helpful aspect of module design—the ease with which something can be composed with other code. Focused modules that compute values are applicable in a wider range of programs than bigger modules that perform complicated actions with side effects. An INI file reader that insists on reading the file from disk is useless in a scenario where the file’s content comes from some other source.

Relatedly, stateful objects are sometimes useful or even necessary, but if something can be done with a function, use a function. Several of the INI file readers on NPM provide an interface style that require you to first create an object, then load the file into your object, and finally use specialized methods to get at the results. This type of thing is common in the object-oriented tradition, and it’s terrible. Instead of making a single function call and moving on, you have to perform the ritual of moving your object through various states. And because the data is now wrapped in a specialized object type, all code that interacts with it has to know about that type, creating unnecessary interdependencies.

Often defining new data structures can’t be avoided—only a few very basic ones are provided by the language standard, and many types of data have to be more complex than an array or a map. But when an array suffices, use an array.

An example of a slightly more complex data structure is the graph from Chapter 7. There is no single obvious way to represent a graph in JavaScript. In that chapter, we used an object whose properties hold arrays of strings—the other nodes reachable from that node.

There are several different pathfinding packages on NPM, but none of them uses this graph format. They usually allow the graph’s edges to have a weight, the cost or distance associated with it, which isn’t possible in our representation.

For example, there’s the dijkstrajs package. A well-known approach to path finding, quite similar to our findRoute function, is called Dijkstra’s algorithm, after Edsger Dijkstra, who first wrote it down. The js suffix is often added to package names to indicate the fact that they are written in JavaScript. This dijkstrajs package uses a graph format similar to ours, but instead of arrays, it uses objects whose property values are numbers—the weights of the edges.

So if we wanted to use that package, we’d have to make sure that our graph was stored in the format it expects.

const {find_path} = require("dijkstrajs"); let graph = {}; for (let node of Object.keys(roadGraph)) { let edges = graph[node] = {}; for (let dest of roadGraph[node]) { edges[dest] = 1; } } console.log(find_path(graph, "Post Office", "Cabin")); // → ["Post Office", "Alice's House", "Cabin"]

This can be a barrier to composition—when various packages are using different data structures to describe similar things, combining them is difficult. Therefore, if you want to design for composability, find out what data structures other people are using and, when possible, follow their example.

Summary

Modules provide structure to bigger programs by separating the code into pieces with clear interfaces and dependencies. The interface is the part of the module that’s visible from other modules, and the dependencies are the other modules that it makes use of.

Because JavaScript historically did not provide a module system, the CommonJS system was built on top of it. Then at some point it did get a built-in system, which now coexists uneasily with the CommonJS system.

A package is a chunk of code that can be distributed on its own. NPM is a repository of JavaScript packages. You can download all kinds of useful (and useless) packages from it.

Exercises

A modular robot

These are the bindings that the project from Chapter 7 creates:

roads buildGraph roadGraph VillageState runRobot randomPick randomRobot mailRoute routeRobot findRoute goalOrientedRobot

If you were to write that project as a modular program, what modules would you create? Which module would depend on which other module, and what would their interfaces look like?

Which pieces are likely to be available pre-written on NPM? Would you prefer to use an NPM package or write them yourself?

Here’s what I would have done (but again, there is no single right way to design a given module):

The code used to build the road graph lives in the graph module. Because I’d rather use dijkstrajs from NPM than our own pathfinding code, we’ll make this build the kind of graph data that dijkstajs expects. This module exports a single function, buildGraph. I’d have buildGraph accept an array of two-element arrays, rather than strings containing dashes, to make the module less dependent on the input format.

The roads module contains the raw road data (the roads array) and the roadGraph binding. This module depends on ./graph and exports the road graph.

The VillageState class lives in the state module. It depends on the ./roads module, because it needs to be able to verify that a given road exists. It also needs randomPick. Since that is a three-line function, we could just put it into the state module as an internal helper function. But randomRobot needs it too. So we’d have to either duplicate it or put it into its own module. Since this function happens to exist on NPM in the random-item package, a good solution is to just make both modules depend on that. We can add the runRobot function to this module as well, since it’s small and closely related to state management. The module exports both the VillageState class and the runRobot function.

Finally, the robots, along with the values they depend on such as mailRoute, could go into an example-robots module, which depends on ./roads and exports the robot functions. To make it possible for the goalOrientedRobot to do route-finding, this module also depends on dijkstrajs.

By offloading some work to NPM modules, the code became a little smaller. Each individual module does something rather simple, and can be read on its own. Dividing code into modules also often suggests further improvements to the program’s design. In this case, it seems a little odd that the VillageState and the robots depend on a specific road graph. It might be a better idea to make the graph an argument to the state’s constructor and make the robots read it from the state object—this reduces dependencies (which is always good) and makes it possible to run simulations on different maps (which is even better).

Is it a good idea to use NPM modules for things that we could have written ourselves? In principle, yes—for nontrivial things like the pathfinding function you are likely to make mistakes and waste time writing them yourself. For tiny functions like random-item, writing them yourself is easy enough. But adding them wherever you need them does tend to clutter your modules.

However, you should also not underestimate the work involved in finding an appropriate NPM package. And even if you find one, it might not work well or may be missing some feature you need. On top of that, depending on NPM packages means you have to make sure they are installed, you have to distribute them with your program, and you might have to periodically upgrade them.

So again, this is a trade-off, and you can decide either way depending on how much the packages help you.

Roads module

Write a CommonJS module, based on the example from Chapter 7, that contains the array of roads and exports the graph data structure representing them as roadGraph. It should depend on a module ./graph, which exports a function buildGraph that is used to build the graph. This function expects an array of two-element arrays (the start and end points of the roads).

// Add dependencies and exports const roads = [ "Alice's House-Bob's House", "Alice's House-Cabin", "Alice's House-Post Office", "Bob's House-Town Hall", "Daria's House-Ernie's House", "Daria's House-Town Hall", "Ernie's House-Grete's House", "Grete's House-Farm", "Grete's House-Shop", "Marketplace-Farm", "Marketplace-Post Office", "Marketplace-Shop", "Marketplace-Town Hall", "Shop-Town Hall" ];

Since this is a CommonJS module, you have to use require to import the graph module. That was described as exporting a buildGraph function, which you can pick out of its interface object with a destructuring const declaration.

To export roadGraph, you add a property to the exports object. Because buildGraph takes a data structure that doesn’t precisely match roads, the splitting of the road strings must happen in your module.

Circular dependencies

A circular dependency is a situation where module A depends on B, and B also, directly or indirectly, depends on A. Many module systems simply forbid this because whichever order you choose for loading such modules, you cannot make sure that each module’s dependencies have been loaded before it runs.

CommonJS modules allow a limited form of cyclic dependencies. As long as the modules do not replace their default exports object, and don’t access each other’s interface until after they finish loading, cyclic dependencies are okay.

The require function given earlier in this chapter supports this type of dependency cycle. Can you see how it handles cycles? What would go wrong when a module in a cycle does replace its default exports object?

The trick is that require adds modules to its cache before it starts loading the module. That way, if any require call made while it is running tries to load it, it is already known and the current interface will be returned, rather than starting to load the module once more (which would eventually overflow the stack).

If a module overwrites its module.exports value, any other module that has received its interface value before it finished loading will have gotten hold of the default interface object (which is likely empty), rather than the intended interface value.