Chapter 21Project: Skill-Sharing Website

If you have knowledge, let others light their candles at it.

A skill-sharing meeting is an event where people with a shared interest come together and give small, informal presentations about things they know. At a gardening skill-sharing meeting, someone might explain how to cultivate celery. Or in a programming skill-sharing group, you could drop by and tell people about Node.js.

Such meetups—also often called users’ groups when they are about computers—are a great way to broaden your horizon, learn about new developments, or simply meet people with similar interests. Many larger cities have a JavaScript meetup. They are typically free to attend, and I’ve found the ones I’ve visited to be friendly and welcoming.

In this final project chapter, our goal is to set up a website for managing talks given at a skill-sharing meeting. Imagine a small group of people meeting up regularly in the office of one of the members to talk about unicycling. The previous organizer of the meetings moved to another town, and nobody stepped forward to take over this task. We want a system that will let the participants propose and discuss talks among themselves, without a central organizer.

Just like in the previous chapter, some of the code in this chapter is written for Node.js, and running it directly in the HTML page that you are looking at is unlikely to work. The full code for the project can be downloaded from eloquentjavascript.net/code/skillsharing.zip.

Design

There is a server part to this project, written for Node.js, and a client part, written for the browser. The server stores the system’s data and provides it to the client. It also serves the files that implement the client-side system.

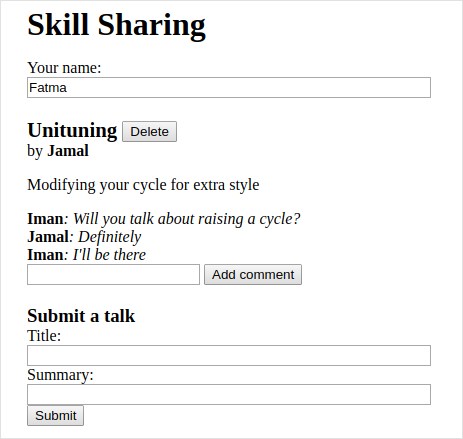

The server keeps the list of talks proposed for the next meeting, and the client shows this list. Each talk has a presenter name, a title, a summary, and an array of comments associated with it. The client allows users to propose new talks (adding them to the list), delete talks, and comment on existing talks. Whenever the user makes such a change, the client makes an HTTP request to tell the server about it.

The application will be set up to show a live view of the current proposed talks and their comments. Whenever someone, somewhere, submits a new talk or adds a comment, all people who have the page open in their browsers should immediately see the change. This poses a bit of a challenge—there is no way for a web server to open a connection to a client, nor is there a good way to know which clients are currently looking at a given website.

A common solution to this problem is called long polling, which happens to be one of the motivations for Node’s design.

Long polling

To be able to immediately notify a client that something changed, we need a connection to that client. Since web browsers do not traditionally accept connections and clients are often behind routers that would block such connections anyway, having the server initiate this connection is not practical.

We can arrange for the client to open the connection and keep it around so that the server can use it to send information when it needs to do so.

But an HTTP request allows only a simple flow of information: the client sends a request, the server comes back with a single response, and that is it. There is a technology called web sockets, supported by modern browsers, which makes it possible to open connections for arbitrary data exchange. But using them properly is somewhat tricky.

In this chapter, we use a simpler technique—long polling—where clients continuously ask the server for new information using regular HTTP requests, and the server stalls its answer when it has nothing new to report.

As long as the client makes sure it constantly has a polling request open, it will receive information from the server quickly after it becomes available. For example, if Fatma has our skill-sharing application open in her browser, that browser will have made a request for updates and be waiting for a response to that request. When Iman submits a talk on Extreme Downhill Unicycling, the server will notice that Fatma is waiting for updates and send a response containing the new talk to her pending request. Fatma’s browser will receive the data and update the screen to show the talk.

To prevent connections from timing out (being aborted because of a lack of activity), long polling techniques usually set a maximum time for each request, after which the server will respond anyway, even though it has nothing to report, after which the client will start a new request. Periodically restarting the request also makes the technique more robust, allowing clients to recover from temporary connection failures or server problems.

A busy server that is using long polling may have thousands of waiting requests, and thus TCP connections, open. Node, which makes it easy to manage many connections without creating a separate thread of control for each one, is a good fit for such a system.

HTTP interface

Before we start designing either the server or the client, let’s think about the point where they touch: the HTTP interface over which they communicate.

We will use JSON as the format of our request and response body. Like in the file server from Chapter 20, we’ll try to make good use of HTTP methods and headers. The interface is centered around the /talks path. Paths that do not start with /talks will be used for serving static files—the HTML and JavaScript code for the client-side system.

A GET request to /talks returns a JSON document like this:

[{"title": "Unituning",

"presenter": "Jamal",

"summary": "Modifying your cycle for extra style",

"comment": []}]}

Creating a new talk is done by making a PUT request to a URL like /talks/Unituning, where the part after the second slash is the title of the talk. The PUT request’s body should contain a JSON object that has presenter and summary properties.

Since talk titles may contain spaces and other characters that may not appear normally in a URL, title strings must be encoded with the encodeURIComponent function when building up such a URL.

console.log("/talks/" + encodeURIComponent("How to Idle")); // → /talks/How%20to%20Idle

A request to create a talk about idling might look something like this:

PUT /talks/How%20to%20Idle HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 92

{"presenter": "Maureen",

"summary": "Standing still on a unicycle"}

Such URLs also support GET requests to retrieve the JSON representation of a talk and DELETE requests to delete a talk.

Adding a comment to a talk is done with a POST request to a URL like /, with a JSON body that has author and message properties.

POST /talks/Unituning/comments HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 72

{"author": "Iman",

"message": "Will you talk about raising a cycle?"}

To support long polling, GET requests to /talks may include extra headers that inform the server to delay the response if no new information is available. We’ll use a pair of headers normally intended to manage caching: ETag and If-None-Match.

Servers may include an ETag (“entity tag”) header in a response. Its value is a string that identifies the current version of the resource. Clients, when they later request that resource again, may make a conditional request by including an If-None-Match header whose value holds that same string. If the resource hasn’t changed, the server will respond with status code 304, which means “not modified”, telling the client that its cached version is still current. When the tag does not match the server responds as normal.

We need something like this, where the client can tell the server which version of the list of talks it has, and the server only responds when that list has changed. But instead of immediately returning a 304 response, the server should stall the response, and only return when something new is available or a given amount of time has elapsed. To distinguish long polling requests from normal conditional requests, we give them another header Prefer: wait=90, which tells the server that the client is willing wait up to 90 seconds for the response.

The server will keep a version number that it updates every time the talks change, and uses that as the ETag value. Clients can make requests like this to be notified when the talks change:

GET /talks HTTP/1.1 If-None-Match: "4" Prefer: wait=90 (time passes) HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Type: application/json ETag: "5" Content-Length: 295 [....]

The protocol described here does not do any access control. Everybody can comment, modify talks, and even delete them. (Since the Internet is full of hooligans, putting such a system online without further protection probably wouldn’t end well.)

The server

Let’s start by building the server-side part of the program. The code in this section runs on Node.js.

Routing

Our server will use createServer to start an HTTP server. In the function that handles a new request, we must distinguish between the various kinds of requests (as determined by the method and the path) that we support. This can be done with a long chain of if statements, but there is a nicer way.

A router is a component that helps dispatch a request to the function that can handle it. You can tell the router, for example, that PUT requests with a path that matches the regular expression / (/talks/ followed by a talk title) can be handled by a given function. In addition, it can help extract the meaningful parts of the path, in this case the talk title, wrapped in parentheses in the regular expression, and pass those to the handler function.

There are a number of good router packages on NPM, but here we’ll write one ourselves to illustrate the principle.

This is router.js, which we will later require from our server module:

const {parse} = require("url"); module.exports = class Router { constructor() { this.routes = []; } add(method, url, handler) { this.routes.push({method, url, handler}); } resolve(context, request) { let path = parse(request.url).pathname; for (let {method, url, handler} of this.routes) { let match = url.exec(path); if (!match || request.method != method) continue; let urlParts = match.slice(1).map(decodeURIComponent); return handler(context, urlParts, request); } return null; } };

The module exports the Router class. A router object allows new handlers to be registered with the add method and can resolve requests with its resolve method.

The latter will return a response when a handler was found, and null otherwise. It tries the routes one at a time (in the order in which they were defined) until a matching one is found.

The handler functions are called with the context value (which will be the server instance in our case), match string for any groups they defined in their regular expression, and the request object. The strings have to be URL-decoded since the raw URL may contain %20-style codes.

Serving files

When a request matches none of the request types defined in our router, the server must interpret it as a request for a file in the public directory. It would be possible to use the file server defined in Chapter 20 to serve such files, but we neither need nor want to support PUT and DELETE requests on files, and we would like to have advanced features such as support for caching. So let’s use a solid, well-tested static file server from NPM instead.

I opted for ecstatic. This isn’t the only such server on NPM, but it works well and fits our purposes. The ecstatic package exports a function that can be called with a configuration object to produce a request handler function. We use the root option to tell the server where it should look for files. The handler function accepts request and response parameters and can be passed directly to createServer to create a server that serves only files. We want to first check for requests that we handle specially, though, so we wrap it in another function.

const {createServer} = require("http"); const Router = require("./router"); const ecstatic = require("ecstatic"); const router = new Router(); const defaultHeaders = {"Content-Type": "text/plain"}; class SkillShareServer { constructor(talks) { this.talks = talks; this.version = 0; this.waiting = []; let fileServer = ecstatic({root: "./public"}); this.server = createServer((request, response) => { let resolved = router.resolve(this, request); if (resolved) { resolved.catch(error => { if (error.status != null) return error; return {body: String(error), status: 500}; }).then(({body, status = 200, headers = defaultHeaders}) => { response.writeHead(status, headers); response.end(body); }); } else { fileServer(request, response); } }); } start(port) { this.server.listen(port); } stop() { this.server.close(); } }

This uses a similar convention as the file server from the previous chapter for responses—handlers return promises that resolve to objects describing the response. It wraps the server in an object that also holds its state.

Talks as resources

The talks that have been proposed are stored in the talks property of the server, an object whose property names are the talk titles. These will be exposed as HTTP resources under /talks/[title], so we need to add handlers to our router that implement the various methods that clients can use to work with them.

The handler for requests that GET a single talk must look up the talk and respond either with the talk’s JSON data or with a 404 error response.

const talkPath = /^\/talks\/([^\/]+)$/; router.add("GET", talkPath, async (server, title) => { if (title in server.talks) { return {body: JSON.stringify(server.talks[title]), headers: {"Content-Type": "application/json"}}; } else { return {status: 404, body: `No talk '${title}' found`}; } });

Deleting a talk is done by removing it from the talks object.

router.add("DELETE", talkPath, async (server, title) => { if (title in server.talks) { delete server.talks[title]; server.updated(); } return {status: 204}; });

The updated method, which we will define later, notifies waiting long polling requests about the change.

To retrieve the content of a request body, we define a function called readStream, which reads all content from a readable stream and returns a promise that resolves to a string.

function readStream(stream) { return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { let data = ""; stream.on("error", reject); stream.on("data", chunk => data += chunk.toString()); stream.on("end", () => resolve(data)); }); }

One handler that needs to read request bodies is the PUT handler, which is used to create new talks. It has to check whether the data it was given has presenter and summary properties which are strings. Any data coming from outside the system might be nonsense, and we don’t want to corrupt our internal data model or crash when bad requests come in.

If the data looks valid, the handler stores an object that represents the new talk in the talks object, possibly overwriting an existing talk with this title, and again calls updated.

router.add("PUT", talkPath, async (server, title, request) => { let requestBody = await readStream(request); let talk; try { talk = JSON.parse(requestBody); } catch (_) { return {status: 400, body: "Invalid JSON"}; } if (!talk || typeof talk.presenter != "string" || typeof talk.summary != "string") { return {status: 400, body: "Bad talk data"}; } server.talks[title] = {title, presenter: talk.presenter, summary: talk.summary, comments: []}; server.updated(); return {status: 204}; });

Adding a comment to a talk works similarly. We use readStream to get the content of the request, validate the resulting data, and store it as a comment when it looks valid.

router.add("POST", /^\/talks\/([^\/]+)\/comments$/, async (server, title, request) => { let requestBody = await readStream(request); let comment; try { comment = JSON.parse(requestBody); } catch (_) { return {status: 400, body: "Invalid JSON"}; } if (!comment || typeof comment.author != "string" || typeof comment.message != "string") { return {status: 400, body: "Bad comment data"}; } else if (title in server.talks) { server.talks[title].comments.push(comment); server.updated(); return {status: 204}; } else { return {status: 404, body: `No talk '${title}' found`}; } });

Trying to add a comment to a nonexistent talk returns a 404 error.

Long polling support

The most interesting aspect of the server is the part that handles long polling. When a GET request comes in for /talks, it may either be a regular request or a long polling request.

There will be multiple places in which we have to send an array of talks to the client, so we first define a helper method that builds up such an array and includes an ETag header in the response.

SkillShareServer.prototype.talkResponse = function() { let talks = []; for (let title of Object.keys(this.talks)) { talks.push(this.talks[title]); } return { body: JSON.stringify(talks), headers: {"Content-Type": "application/json", "ETag": `"${this.version}"`} }; };

The handler itself needs to look at the request headers to see whether If-None-Match and Prefer headers are present. Node stores headers, whose names are specified to be case-insensitive, under their lowercase names.

router.add("GET", /^\/talks$/, async (server, request) => { let tag = /"(.*)"/.exec(request.headers["if-none-match"]); let wait = /\bwait=(\d+)/.exec(request.headers["prefer"]); if (!tag || tag[1] != server.version) { return server.talkResponse(); } else if (!wait) { return {status: 304}; } else { return server.waitForChanges(Number(wait[1])); } });

If no tag was given, or a tag was given that doesn’t match the server’s current version, the handler responds with the list of talks. If the request is conditional and the talks did not change, we consult the Prefer header to see if we should delay the response or respond right away.

Callback functions for delayed requests are stored in the server’s waiting array, so that they can be notified when something happens. The waitForChanges method also immediately sets a timer to respond with a 304 status when the request has waited long enough.

SkillShareServer.prototype.waitForChanges = function(time) { return new Promise(resolve => { this.waiting.push(resolve); setTimeout(() => { if (!this.waiting.includes(resolve)) return; this.waiting = this.waiting.filter(r => r != resolve); resolve({status: 304}); }, time * 1000); }); };

Registering a change with updated increases the version property and wakes up all waiting requests.

SkillShareServer.prototype.updated = function() { this.version++; let response = this.talkResponse(); this.waiting.forEach(resolve => resolve(response)); this.waiting = []; };

That concludes the server code. If we create an instance of SkillShareServer and start it on port 8000, the resulting HTTP server serves files from the public subdirectory alongside a talk-managing interface under the /talks URL.

new SkillShareServer(Object.create(null)).start(8000);

The client

The client-side part of the skill-sharing website consists of three files: a tiny HTML page, a style sheet, and a JavaScript file.

HTML

It is a widely used convention for web servers to try to serve a file named index.html when a request is made directly to a path that corresponds to a directory. The file server module we use, ecstatic, supports this convention. When a request is made to the path /, the server looks for the file ./ (./public being the root we gave it) and returns that file if found.

Thus, if we want a page to show up when a browser is pointed at our server, we should put it in public/. This is our index file:

<meta charset="utf-8"> <title>Skill Sharing</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="skillsharing.css"> <h1>Skill Sharing</h1> <script src="skillsharing_client.js"></script>

It defines the document title and includes a style sheet, which defines a few styles to, among other things, make sure there is some space between talks.

At the bottom, it adds a heading at the top of the page and loads the script that contains the client-side application.

Actions

The application state consists of the list of talks and the name of the user, and we’ll store it in a {talks, user} object. We don’t allow the user interface to directly manipulate the state or send off HTTP requests. Rather, it may emit actions, which describe what the user is trying to do.

The handleAction function takes such an action and makes it happen. Because our state updates are so simple, state changes are handled in the same function.

function handleAction(state, action) { if (action.type == "setUser") { localStorage.setItem("userName", action.user); return Object.assign({}, state, {user: action.user}); } else if (action.type == "setTalks") { return Object.assign({}, state, {talks: action.talks}); } else if (action.type == "newTalk") { fetchOK(talkURL(action.title), { method: "PUT", headers: {"Content-Type": "application/json"}, body: JSON.stringify({ presenter: state.user, summary: action.summary }) }).catch(reportError); } else if (action.type == "deleteTalk") { fetchOK(talkURL(action.talk), {method: "DELETE"}) .catch(reportError); } else if (action.type == "newComment") { fetchOK(talkURL(action.talk) + "/comments", { method: "POST", headers: {"Content-Type": "application/json"}, body: JSON.stringify({ author: state.user, message: action.message }) }).catch(reportError); } return state; }

We’ll store the user’s name in localStorage, so that it can be restored when the page is loaded.

The actions that need to involve the server make network requests, using fetch, to the HTTP interface we described earlier. We use a wrapper function, fetchOK, which makes sure the returned promise is rejected when the server returns an error code.

function fetchOK(url, options) { return fetch(url, options).then(response => { if (response.status < 400) return response; else throw new Error(response.statusText); }); }

And this helper function is used to build up a URL for a talks with a given title.

function talkURL(title) { return "talks/" + encodeURIComponent(title); }

When the request fails, we don’t want to have our page just sit there, doing nothing without explanation. So we define a function called reportError, which at least shows the user a dialog that tells them something went wrong.

function reportError(error) { alert(String(error)); }

Rendering components

We’ll use an approach similar to the one we saw in Chapter 19, splitting the application into components. But since some of the components either never need to update or are always fully redrawn when updated, we’ll define those not as classes, but as functions that directly return a DOM node. For example, here is a component that shows the field where the user can enter their name:

function renderUserField(name, dispatch) { return elt("label", {}, "Your name: ", elt("input", { type: "text", value: name, onchange(event) { dispatch({type: "setUser", user: event.target.value}); } })); }

The elt function used to construct DOM elements is the one we used in Chapter 19.

A similar function is used to render talks, which include a list of comments and a form for adding a new comment.

function renderTalk(talk, dispatch) { return elt( "section", {className: "talk"}, elt("h2", null, talk.title, " ", elt("button", { type: "button", onclick() { dispatch({type: "deleteTalk", talk: talk.title}); } }, "Delete")), elt("div", null, "by ", elt("strong", null, talk.presenter)), elt("p", null, talk.summary), talk.comments.map(renderComment), elt("form", { onsubmit(event) { event.preventDefault(); let form = event.target; dispatch({type: "newComment", talk: talk.title, message: form.elements.comment.value}); form.reset(); } }, elt("input", {type: "text", name: "comment"}), " ", elt("button", {type: "submit"}, "Add comment"))); }

The "submit" event handler calls form.reset to clear the form’s content after creating a "newComment" action.

When creating moderately complex pieces of DOM, this style of programming starts to look rather messy. There’s a widely used (non-standard) JavaScript extension called JSX that lets you write HTML directly in your scripts, which can make such code prettier (depending on what you consider pretty). Before you can actually run such code, you have to run a program on your script to converts the pseudo-HTML into JavaScript function calls much like the ones we use here.

Comments are simpler to render.

function renderComment(comment) { return elt("p", {className: "comment"}, elt("strong", null, comment.author), ": ", comment.message); }

And finally, the form that the user can use to create a new talk is rendered like this.

function renderTalkForm(dispatch) { let title = elt("input", {type: "text"}); let summary = elt("input", {type: "text"}); return elt("form", { onsubmit(event) { event.preventDefault(); dispatch({type: "newTalk", title: title.value, summary: summary.value}); event.target.reset(); } }, elt("h3", null, "Submit a Talk"), elt("label", null, "Title: ", title), elt("label", null, "Summary: ", summary), elt("button", {type: "submit"}, "Submit")); }

Polling

To start the app we need the current list of talks. Since the initial load is closely related to the long polling process—the ETag from the load must be used when polling—we’ll write a function that keeps polling the server for /talks, and calls a callback function when a new set of talks is available.

async function pollTalks(update) { let tag = undefined; for (;;) { let response; try { response = await fetchOK("/talks", { headers: tag && {"If-None-Match": tag, "Prefer": "wait=90"} }); } catch (e) { console.log("Request failed: " + e); await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 500)); continue; } if (response.status == 304) continue; tag = response.headers.get("ETag"); update(await response.json()); } }

This is an async function, so that looping and waiting for the request is easier. It runs an infinite loop that, on each iteration, retrieves the list of talks—either normally or, if this isn’t the first request, with the headers included that make it a long polling request.

When a request fails, the function waits a moment, and then tries again. This way, if your network connection goes away for a while and then comes back, the application can recover and continue updating. The promise resolved via setTimeout is a way to force the async function to wait.

When the server gives back a 304 response, that means a long polling request timed out, so the function should just immediately start the next request. If the response is a normal 200 response, its body is read as JSON and passed to the callback, and its ETag header value stored for the next iteration.

The application

The following component ties the whole user interface together.

class SkillShareApp { constructor(state, dispatch) { this.dispatch = dispatch; this.talkDOM = elt("div", {className: "talks"}); this.dom = elt("div", null, renderUserField(state.user, dispatch), this.talkDOM, renderTalkForm(dispatch)); this.setState(state); } setState(state) { if (state.talks != this.talks) { this.talkDOM.textContent = ""; for (let talk of state.talks) { this.talkDOM.appendChild( renderTalk(talk, this.dispatch)); } this.talks = state.talks; } } }

When the talks change, this component redraws all of them. This is simple, but also wasteful. We’ll get back to that in the exercises.

We can start the application like this:

function runApp() { let user = localStorage.getItem("userName") || "Anon"; let state, app; function dispatch(action) { state = handleAction(state, action); app.setState(state); } pollTalks(talks => { if (!app) { state = {user, talks}; app = new SkillShareApp(state, dispatch); document.body.appendChild(app.dom); } else { dispatch({type: "setTalks", talks}); } }).catch(reportError); } runApp();

If you run the server and open two browser windows for localhost:8000 next to each other, you can see that the actions you perform in one window are immediately visible in the other.

Exercises

The following exercises will involve modifying the system defined in this chapter. To work on them, make sure you download the code first (eloquentjavascript.net/code/skillsharing.zip), have Node installed nodejs.org, and have installed the project’s dependency with npm install.

Disk persistence

The skill-sharing server keeps its data purely in memory. This means that when it crashes or is restarted for any reason, all talks and comments are lost.

Extend the server so that it stores the talk data to disk and automatically reloads the data when it is restarted. Do not worry about efficiency—do the simplest thing that works.

The simplest solution I can come up with is to encode the whole talks object as JSON and dump it to a file with writeFile. There is already a method (updated) that is called every time the server’s data changes. It can be extended to write the new data to disk.

Pick a filename, for example ./talks.json. When the server starts, it can try to read that file with readFile, and if that succeeds, the server can use the file’s contents as its starting data.

Beware, though. The talks object started as a prototype-less object so that the in operator could reliably be used. JSON.parse will return regular objects with Object.prototype as their prototype. If you use JSON as your file format, you’ll have to copy the properties of the object returned by JSON.parse into a new, prototype-less object.

Comment field resets

The wholesale redrawing of talks works pretty well because you usually can’t tell the difference between a DOM node and its identical replacement. But there are exceptions. If you start typing something in the comment field for a talk in one browser window and then, in another, add a comment to that talk, the field in the first window will be redrawn, removing both its content and its focus.

In a heated discussion, where multiple people are adding comments at the same time, this would be very annoying. Can you come up with a way to solve it?

The best way to do this is probably to make talks component objects, with a setState method, so that they can be updated to show a modified version of the talk. During normal operation, the only way a talk can be changed is by adding more comments, so the setState method can be relatively simple.

The difficult part is that, when a changed list of talks comes in, we have to reconcile the existing list of DOM components with the talks on the new list—deleting components whose talk was deleted, and updating components whose talk changed.

To do this, it might be helpful to keep a data structure that stores the talk components under the talk titles, so that you can easily figure out whether a component exists for a given talk. You can then loop over the new array of talks, and for each of them, either synchronize an existing component or create a new one. To delete components for deleted talks, you’ll have to also loop over the components, and check whether the corresponding talks still exist.